Three-year current study offers insight into Antarctic ice melting

- User stories

Synopsis

Challenge

Melting ice in Antarctica is contributing to global sea level rise. Understanding how warmer waters move from off the continental shelf melt and thin these ice shelves is key to making better predictions and mitigating the impacts.

Solution

Researchers at the University of Bergen, as part of a larger project, used a Nortek Signature 55 to quantify current speed and direction over a 600m profile. The Signature collected data every two hours for over three years, without requiring intervention or external power.

Benefit

These data, combined with insights from other sensors and researchers, will help paint a clear picture of the processes that transport heat towards ice shelves. Better understanding these processes allows for better predictions of future implications of sea level rise.

Researching Antarctic sea ice and sea level rise

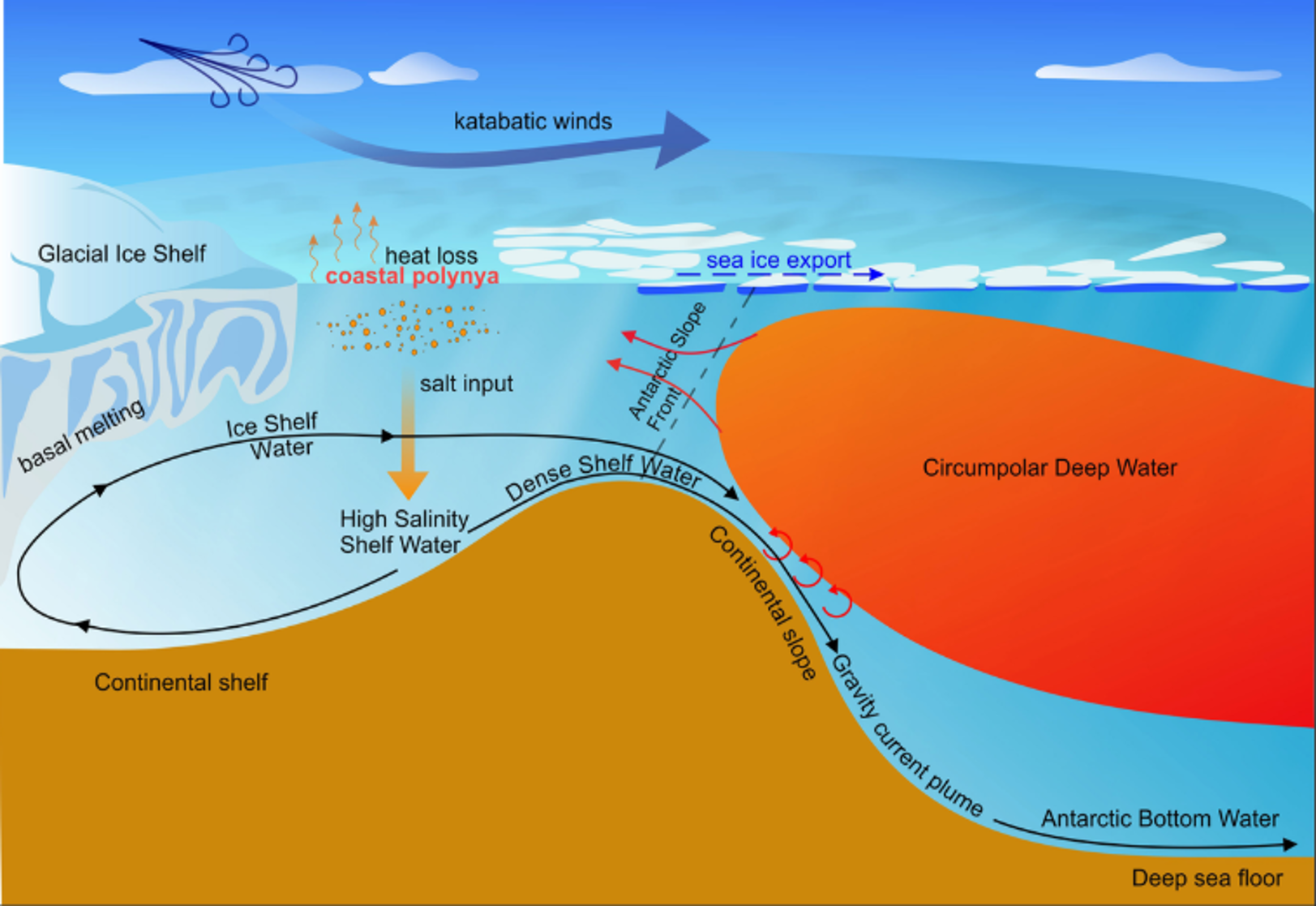

Understanding sea level rise is of increasing importance to coastal communities worldwide. A major factor in sea level rise is the melting of Antarctic ice shelves. Warmer waters interacting with these ice shelves can cause them to calve, creating icebergs and speeding up melting processes, in turn contributing to global sea level rise.

Researchers at the University of Bergen and numerous other scientific institutes worldwide are conducting a multi-year, multi-phase research project aimed at better understanding these processes.

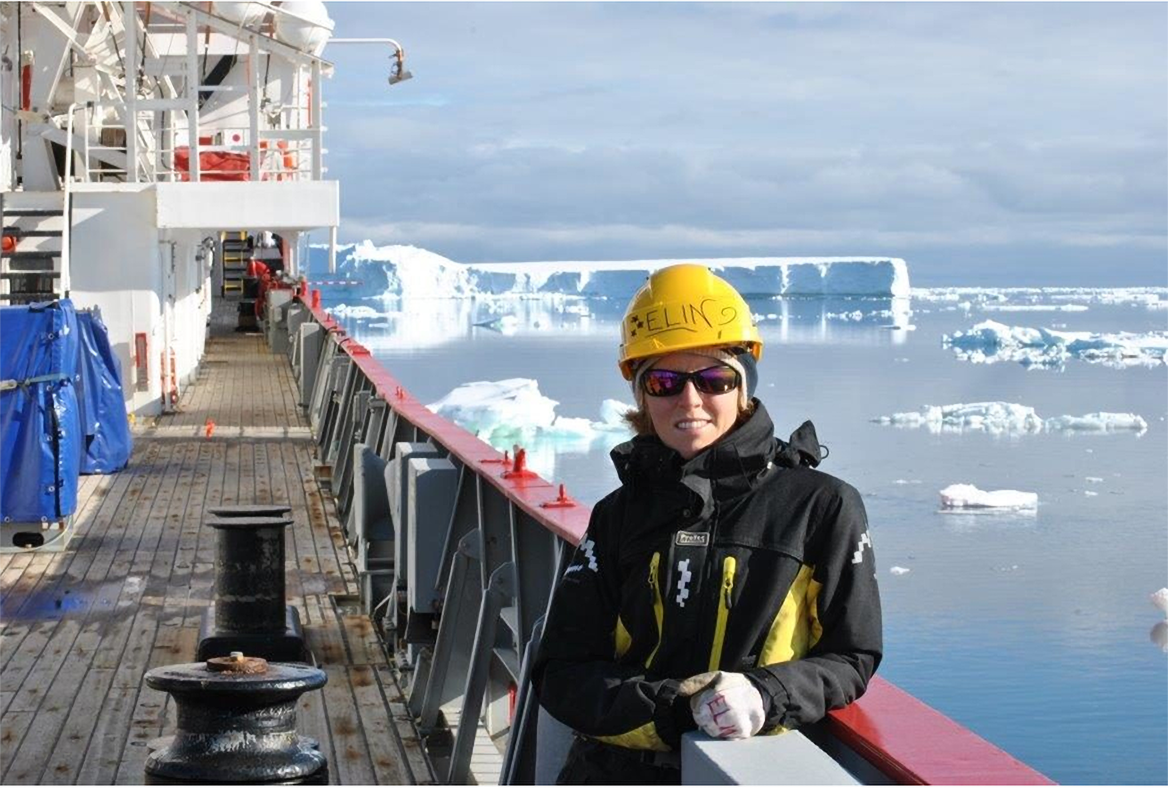

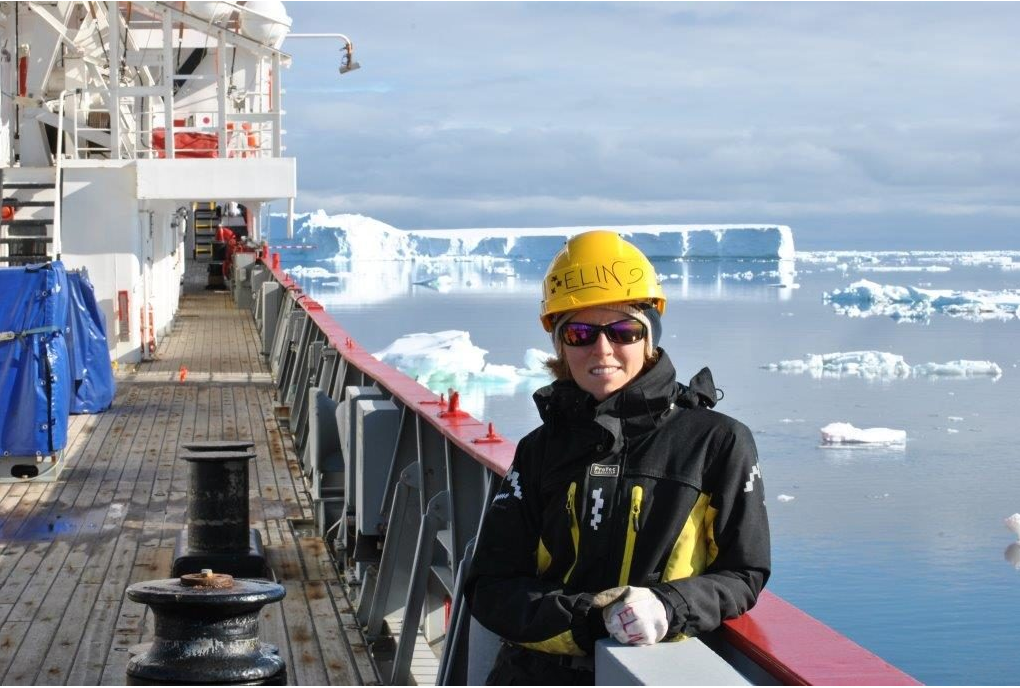

“One large question when it comes to oceanography in Antarctica is the question of oceanic heat transport,” says Dr. Elin Darelius, Professor of Physical Oceanography at the University of Bergen. “That is, heat from the deep ocean that is transported onto the continental shelf and then southward towards the ice shelf cavities, where it can then melt the ice.”

According to Darelius, if these ice shelves melt or thin, the transport of once-grounded ice into the ocean will accelerate, causing sea levels to rise. As part of a team of researchers across Europe, she is aiming to quantify this oceanic heat transfer and identify the key processes involved.

Working across institutions to answer connected questions

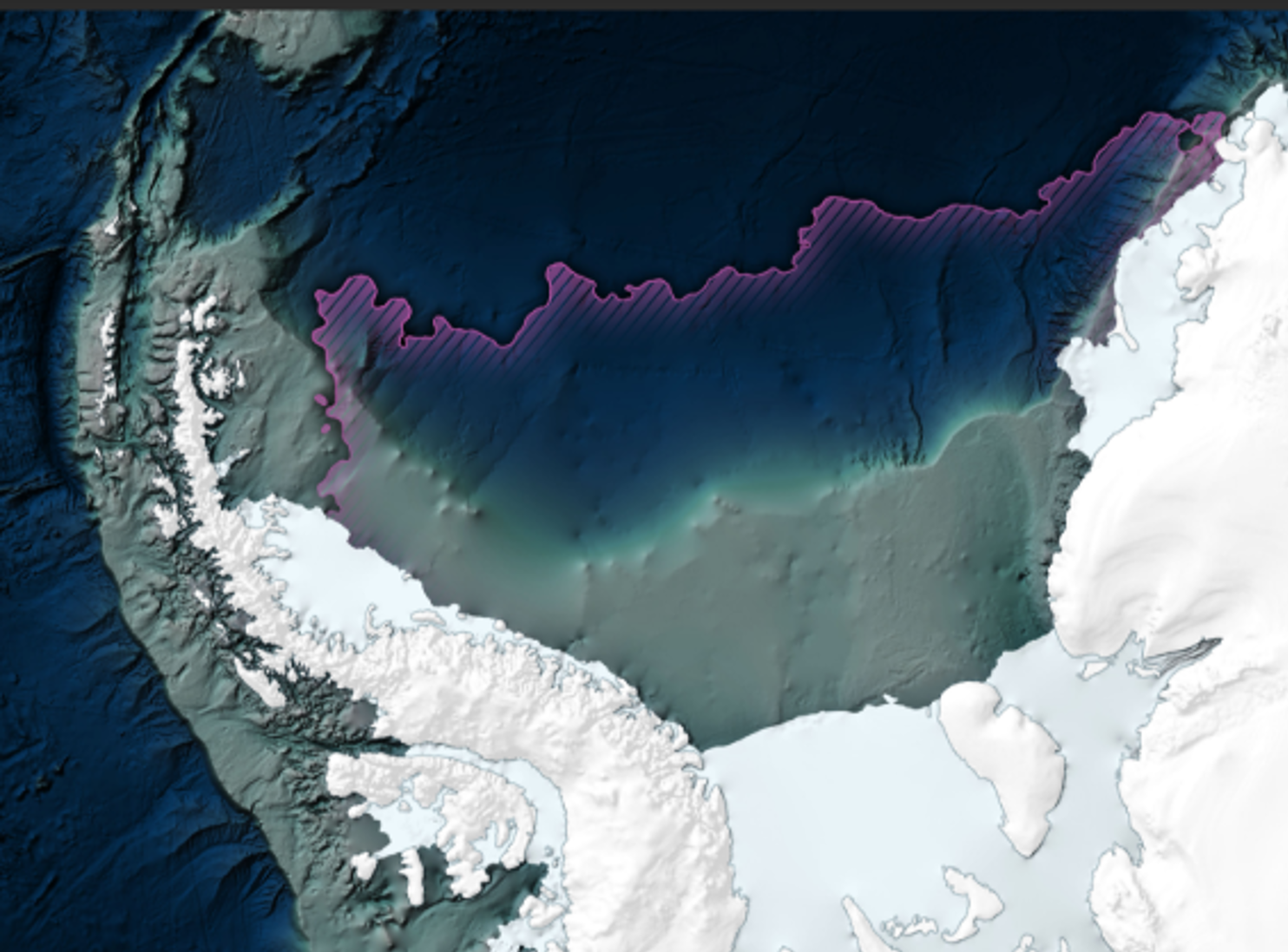

The researchers have a network of moorings across the southeastern Weddell Sea. Darelius has moorings on the continental slope, but her colleagues are also collecting data on the continental shelf as well as within the ice shelf cavity. By investigating oceanographic processes at different locations throughout the Weddell Sea along the path of warm water intrusions, they can paint a more complete picture of how variability in the Antarctic Slope Front propagates onto the continental shelf.

“A front is an area where ocean properties, typically density, change rapidly,” Darelius explains. “In the southern Weddell Sea, we have relatively cold water on the shelf, and then you have warmer water off the shelf: that’s a front. There is a density gradient, so then you get a pressure gradient, and in turn, you get a current associated with this front.”

Because of this front, the amount of warm water coming from off the continental shelf that reaches the shelf is limited. Darelius’ main research objective is to understand how this front evolves with the seasons and with other changes in hydrography, such as sea ice anomalies.

Measuring currents in Antarctic waters for over three years, without requiring external power

To investigate these questions, Darelius gathered information on current speed and direction, as well as other parameters, in the Weddell Sea. Darelius first deployed two moorings on the upper continental slope in 2017. In 2021, one of these moorings was equipped with a Nortek Signature 55 Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler (ADCP). The Signature 55 is designed to gather current velocity measurements over very long distances, with a maximum measurement range of over 1000 m.

The Signature was deployed in March 2021, along with conductivity, temperature and depth sensors (CTDs). The instrument was installed at close to 700 m depth, about 20 m above the seafloor, mounted in a subsurface buoy. It was set to collect current measurements for six minutes every two hours.

The Signature 55 was able to continue collecting data at these intervals for over three years of the deployment, without requiring any external power. Darelius used internal lithium batteries to power the Signature and worked with Nortek ahead of time to determine power requirements. Because of the remote nature of the area, being able to sustain a long deployment was a key requirement of Darelius’ equipment.

The moorings were recovered in January 2025 for the data analysis to begin.

ADCP data tells a story of floating ice

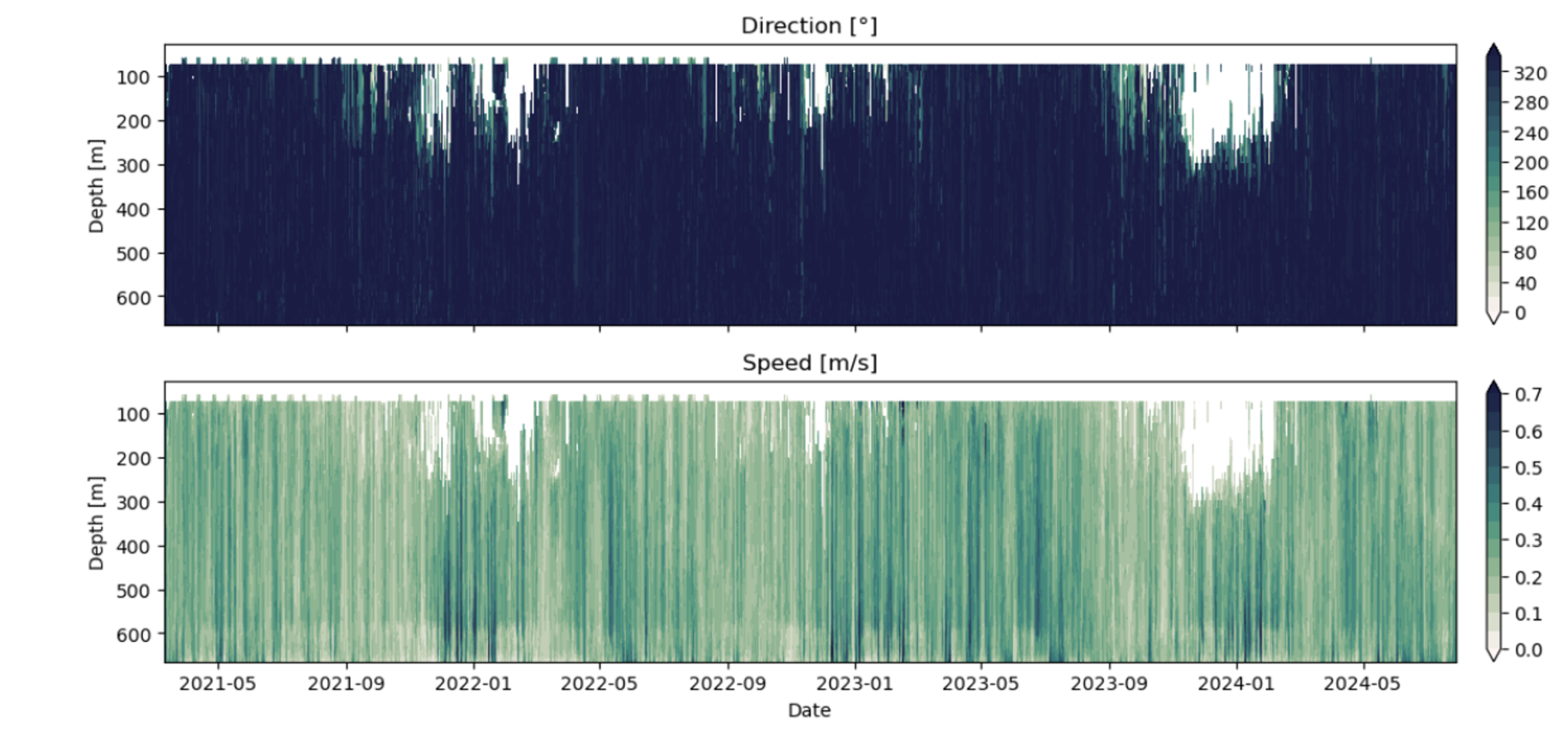

The data shown in image 6 are from the Signature 55 deployment, spanning 2021 to 2024. Image 6 shows current speed and direction over the 600-m profile. Seasonal variations in current speed are present, with faster current speeds being recorded in the summertime.

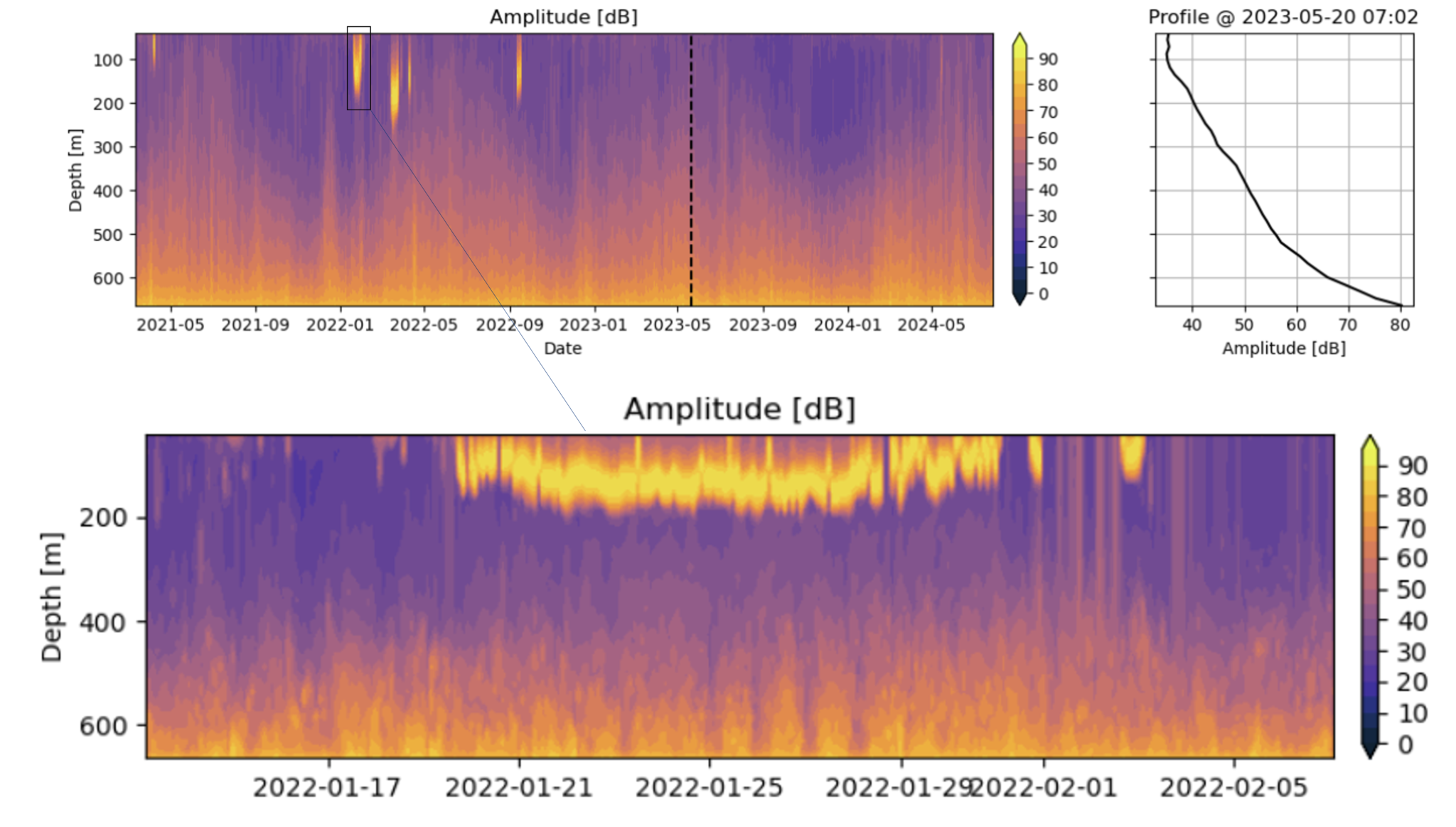

ADCPs rely on sound to take current measurements. Image 7 shows amplitude: the strength of the sound signal returned to the ADCP. Stronger return is typical closer to the instrument, but big changes in amplitude farther from the instrument can mean interference from objects present in the water column.

These large spikes in amplitude and areas where currents couldn’t be collected close to the surface in the summertime paint a picture of icebergs breaking off from ice shelves upstream and drifting past the instrument.

Darelius will use these data to paint a picture of how warmer waters from off the continental shelf move towards the ice shelf, and how these currents change seasonally or with other changes in conditions.

Antarctic research: key to making better predictions about climate change

The data retrieved in 2025 will be analyzed alongside data from a previous deployment spanning 2017-2021 as well as the data collected by researchers at other institutions, including the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI), LOCEAN, the University of Gothenberg, and NORCE. Darelius and other members of the team are heading back to the Weddell Sea in December 2025 to begin the next phase of the project, where they aim to recover other moorings as well as do further work in an area upstream from the site of the Signature 55.

Darelius notes the importance of work like this to protect communities from the impacts of climate change.

“When it comes to predicting the future of sea level rise, there’s a large uncertainty in the timing and quantity of Antarctic contribution,” she explains. “There’s so much we don’t understand with respect to both what the ocean will do, but of course also the ice on land. Everything we learn about this system will hopefully reduce the uncertainty in the projections.”