Oceanographic data of extraordinary quality made possible by integration of ADCP on underwater glider

- User stories

Synopsis

Challenge

Gliders, like Alseamar’s SeaExplorer, are essential to quantify currents over large volumes of the ocean – but measuring currents while the glider in motion is notoriously complicated.

Solution

Nortek and Alseamar collaborated to equip the gliders with adapted ADCPs designed specifically to combat the challenges associated with glider descent and ascent.

Benefit

High-resolution current data is collected by the gliders during all stages of the mission, providing a more comprehensive picture of large-scale ocean processes.

Acoustic Doppler current profilers (ADCPs) have revolutionized our ability to record ocean current movements. But they can only measure what they can “see”, and that is largely determined by what they are attached to, which may be a surface buoy or a frame on the seabed.

That’s perfect for many uses, but if you are seeking to find out about the movements of currents across a large swathe of ocean, then moving ADCPs on frames from location to location is a time-consuming business and doesn’t provide a complete picture of the currents in the whole area. Mounting an ADCP on a moving surface vessel is a good option for many, but some users are put off by the work and cost involved with hiring and crewing a vessel.

Underwater gliders and ADCPs – an efficient and cost-effective way to profile a large volume of water

However, rapid advances in underwater glider technology have provided an exciting new alternative. Slimline battery-powered gliders are capable of cruising through the oceans for months at a time, carrying a multitude of instruments measuring many facets of the underwater world close up.

Typically, gliders move in a sawtooth, or wave-like, movement between the top of the water column and depths of around 1000 m. So, if you can get accurate measurements from an ADCP fixed to a glider, you have an efficient and cost-effective way to profile a huge volume of water in a relatively short period of time.

That possibility prompted researchers at French marine tech company Alseamar to investigate how an ADCP could be made to work with their SeaExplorer glider. The company produces high-tech marine and submarine equipment, such as gliders (or UUVs – underwater unmanned vehicles) with very long mission endurance.

Their investigation of ADCPs was accelerated when Alseamar researchers joined the CITEPH innovation program in 2015. The research was done in collaboration with French energy firm Total and two French academic research laboratories, with Nortek eventually providing the ADCP as the project continued. Total describes the glider program as a success, saying that the innovation that came as a result of it was “a world first in the deep offshore, [making] our exploration more efficient while cutting costs and HSE risks”.

Access to highly accurate data on how our oceans work

Today, the SeaExplorer – equipped with a specially adapted 1 MHz OEM (original equipment manufacturer) version of a Nortek ADCP and a multitude of other instruments – is being used by Alseamar and its customers around the world. It is proving to be a versatile autonomous vehicle, well equipped for application in scientific research, military deployments and commercial subsea operations such as oil and gas exploration.

The results benefit all of us. The detailed analysis of current movements made possible by the Nortek ADCP, combined with data from the glider’s other instruments, gives users access to highly accurate data on how our oceans work. That enhances our understanding of human impact on the marine environment – enabling us, for example, to monitor the effects of climate change on the ocean, and understand the interaction between structures such as oil and gas rigs, offshore wind turbines or coastal infrastructure with the surrounding subsea world.

Video: See how Ecopetrol used a fleet of SeaExplorer underwater gliders in the Colombian Caribbean to acquire in-situ data at sea and support its offshore activities. (Video courtesy of Ecopetrol.)

“Glider missions contribute to the international efforts of the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS),” says Orens de Fommervault, oceanographer at Alseamar.

The UNESCO-led GOOS program coordinates observations in the ocean globally, focusing on three critical themes: climate, operational services and marine ecosystem health.

“It brings together marine scientists and engineers operating gliders around the world to observe the long-term physical, biogeochemical and biological ocean processes and phenomena that are relevant for societal application,” he explains.

“The most widespread applications are boundary currents, tropical and extratropical storms and water-masses transformations. In these three key areas of focus, measurements of currents in the ocean [with ADCPs] are of particular interest,” de Fommervault adds.

An ideal current profiler for underwater gliders

Nortek’s 1 MHz current profiler was an attractive option for Alseamar due to a multitude of reasons.

“The Nortek ADCP design is really ideal for a profiling platform like ours. You could almost say it was dedicated to our application,” says Orens de Fommervault, who is the oceanographer at Alseamar leading the ADCP glider integration project.

This project truly breaks new ground in the oceanographic research industry. Some select academic institutions are also able to estimate water currents from a glider, but the real step forward is that this is now available as a service from a private company.

“Glider-mounted ADCPs offer the ability to collect high-resolution, dense-data water velocity measurements at an unprecedented spatio-temporal scale resolution without the constant use and expense of support vessels,” de Fommervault points out.

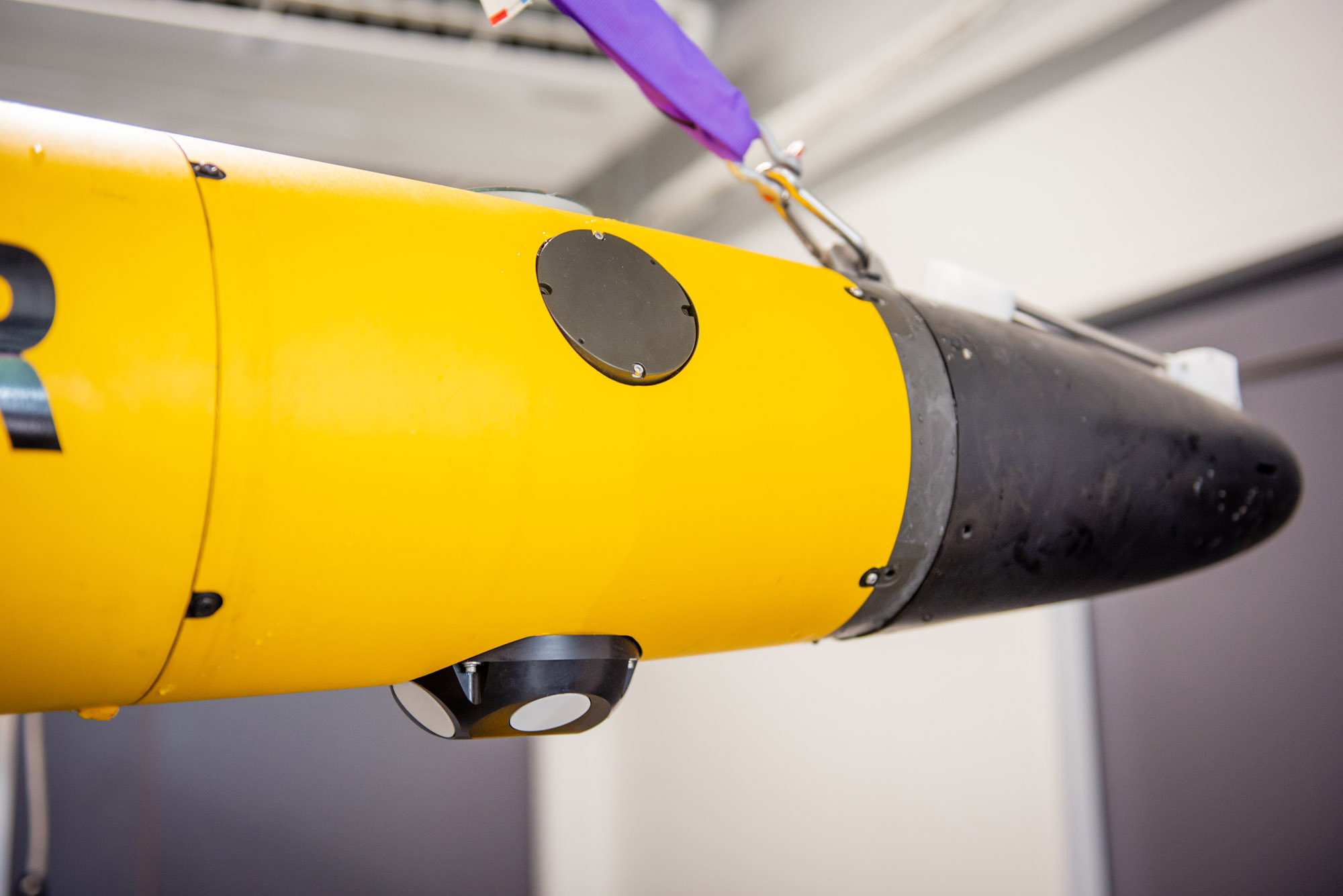

The geometry of the ADCP’s four transducers, which are angled away from each other, means that the instrument can measure more of the water column on its angled trajectory than if the transducers were all oriented in the same direction.

This also means they can carry out current profiling measurements when the glider is rising back to the surface, as well as when it is diving – effectively doubling the amount of information that can be gathered compared to other ADCPs that can only take accurate measurements when diving (see Figure 1).

The relatively small size and low power consumption of Nortek’s ADCP are also plus points when you are seeking to pack as much instrumentation on to a glider as possible and get the most out of its on-board battery.

Integrating the ADCP and accurately interpreting oceanographic data from the moving glider

Alseamar collaborated closely with Nortek in the early days of the project.

“When we wanted to improve our capabilities with more accurate estimations of the backscatter index, vertical velocity and so on, we had a lot of interaction with Nortek to get their expertise. We were very happy with the collaboration. I got fast responses with exactly the answers I needed,” says Orens de Fommervault.

But selecting the right ADCP was only the start of the task for the Alseamar team. Processing data gathered from a glider moving at an angle through the water column to give accurate current profiles is far from easy.

“We worked for almost a year on integrating the ADCP on the glider. We wanted to give the end user an opportunity to tune the many adjustable parameters to meet their scientific objectives,” says Orens de Fommervault.

First, the ADCP needed to be fitted onto the SeaExplorer, a glider packed with instruments, where space was at a premium.

Then the team came up with a configuration for the ADCP that represented a good compromise between the current profiler’s sampling rate and the velocity and angle of the glider’s trajectory, so that it provided good coverage (or sampling) over the entire water column.

The next step was to develop an algorithm that could accurately interpret data harvested from a moving glider.

The results have been impressive, with the processed data from the ADCP on the glider comparing well with that from fixed-point-mounted and vessel-mounted current profilers.

In a separate project, the team was also able to use the ADCP’s ability to estimate the glider’s motion in relation to the surrounding water (under certain assumptions) to fine-tune the hydrodynamic model, which describes how the glider moves through and interacts with the water.

ADCP-equipped glider proves accuracy in a number of different environments

The ADCP-equipped glider has proved its accuracy in a number of different environments.

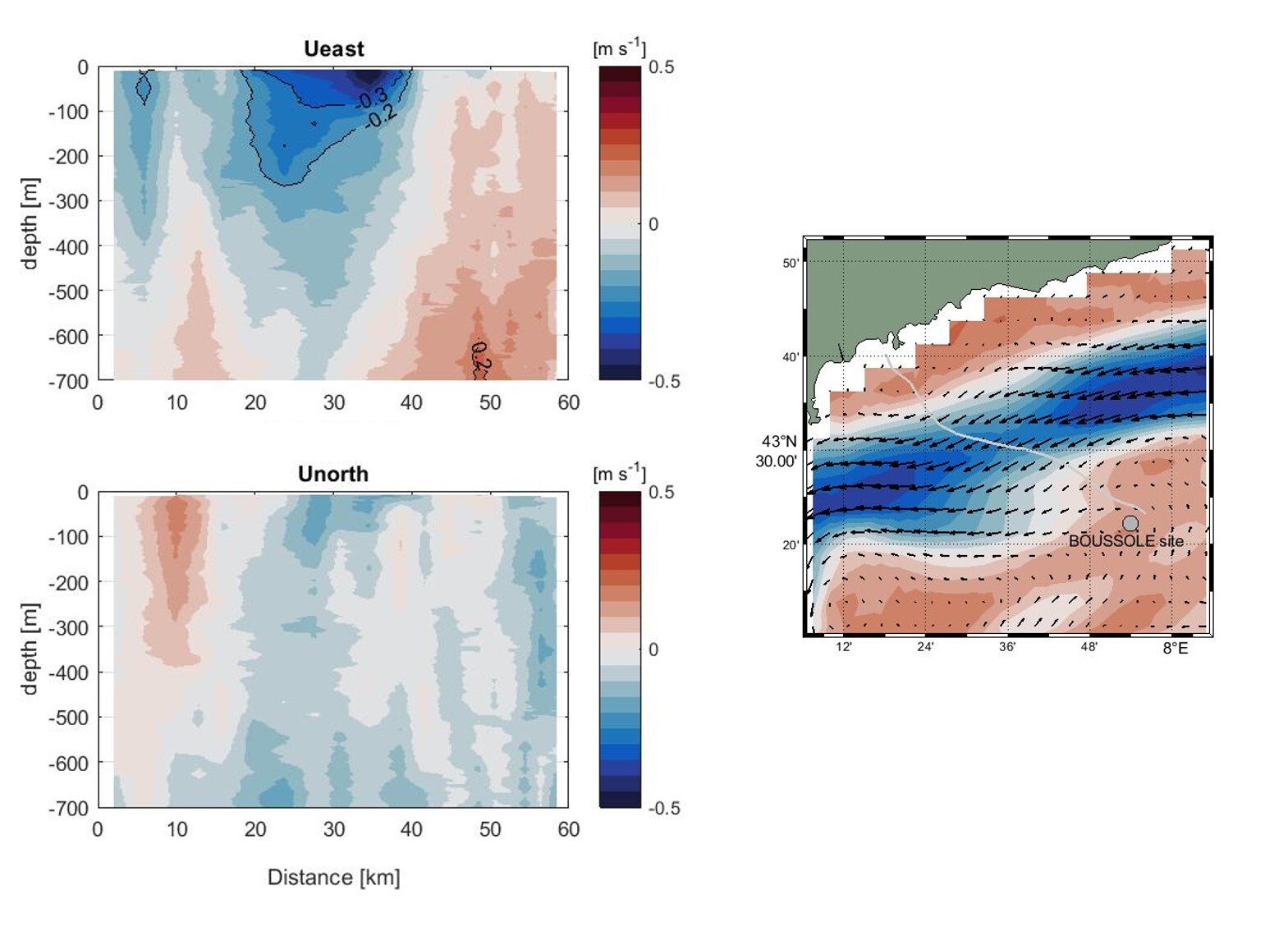

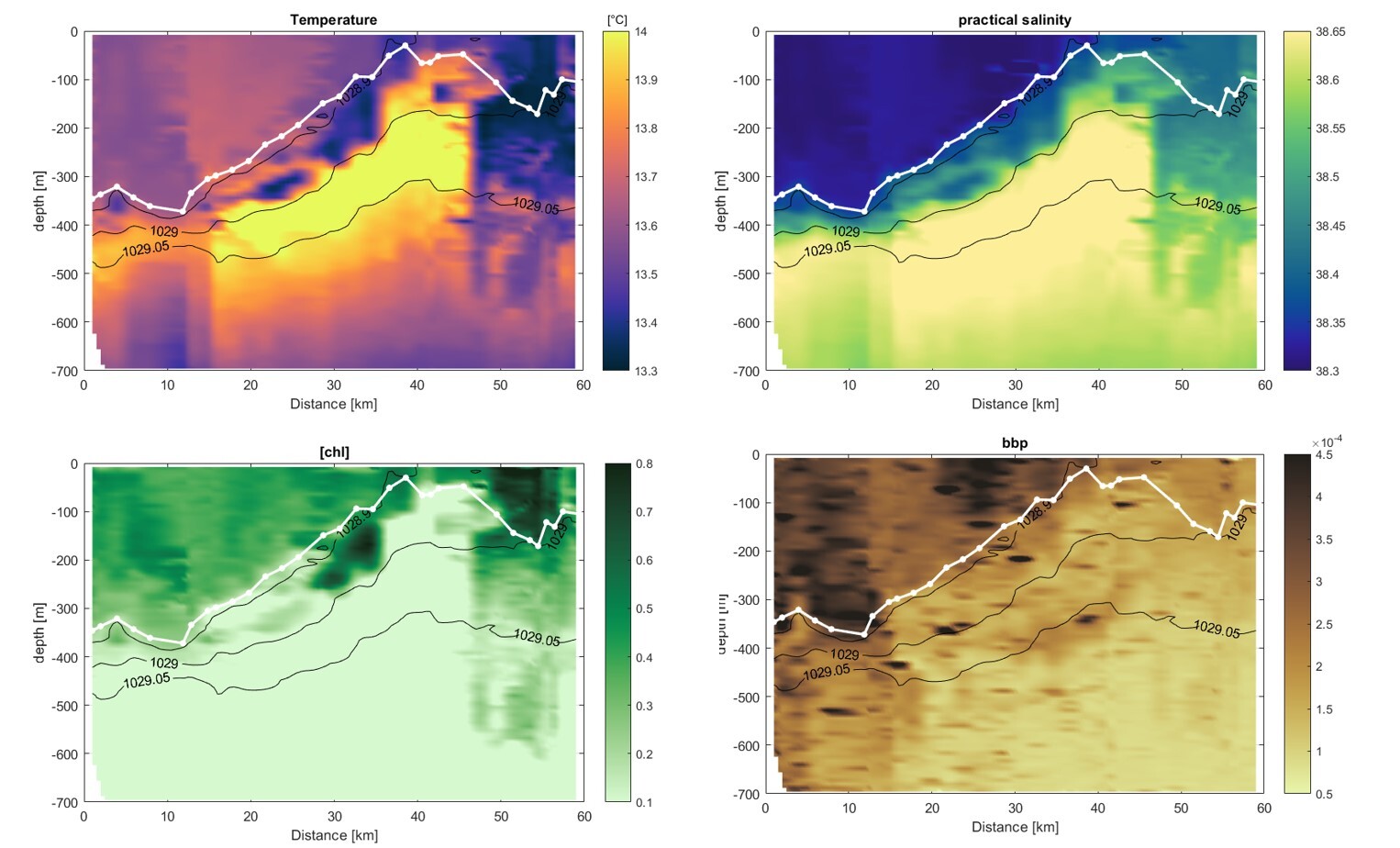

Figures 2 and 3 show how current profiles obtained by the ADCP on the SeaExplorer glider across 60 km in the Mediterranean Sea off southern France correlate with temperature, salinity and chlorophyll measurements taken by the glider at the same time.

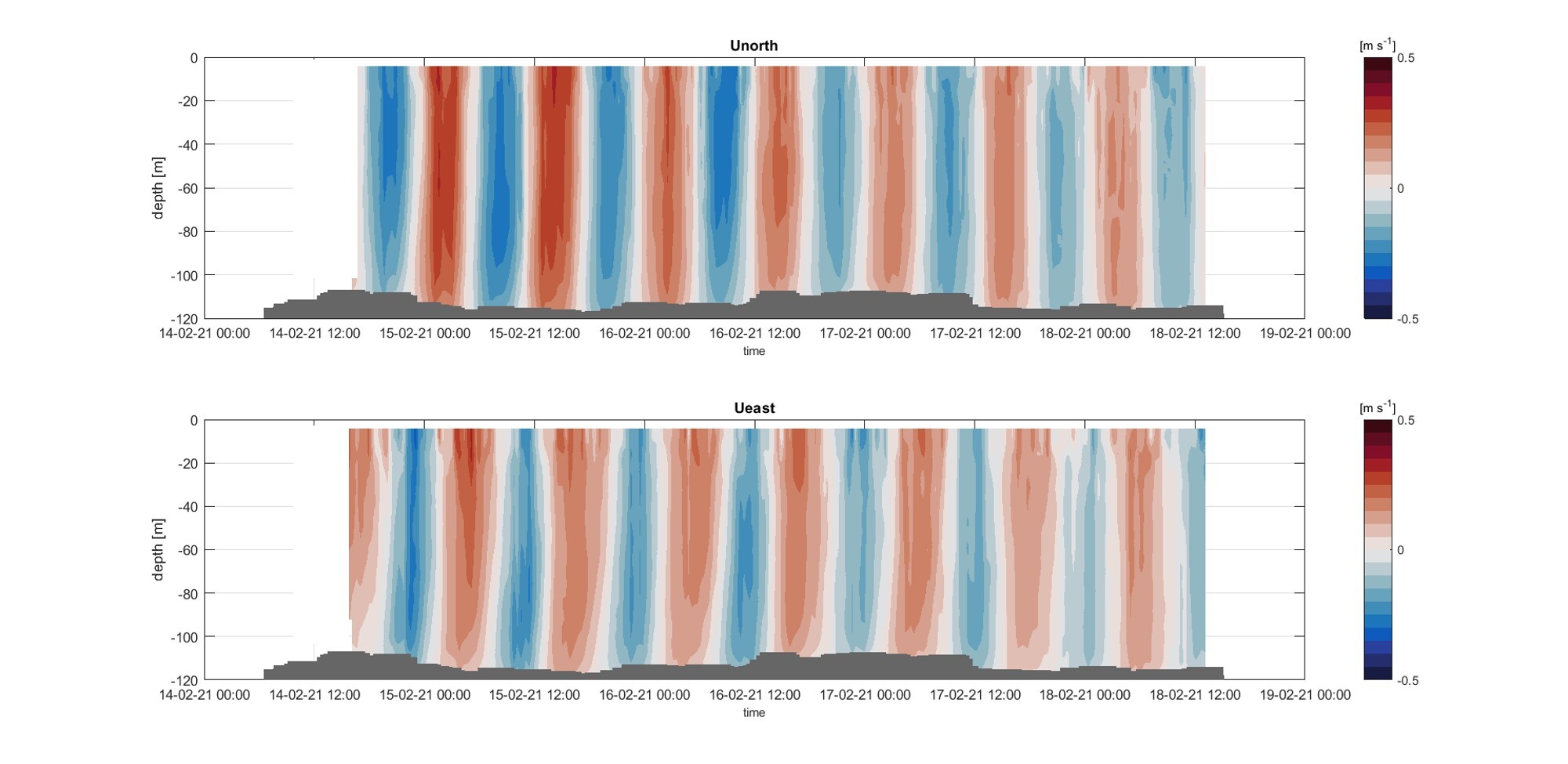

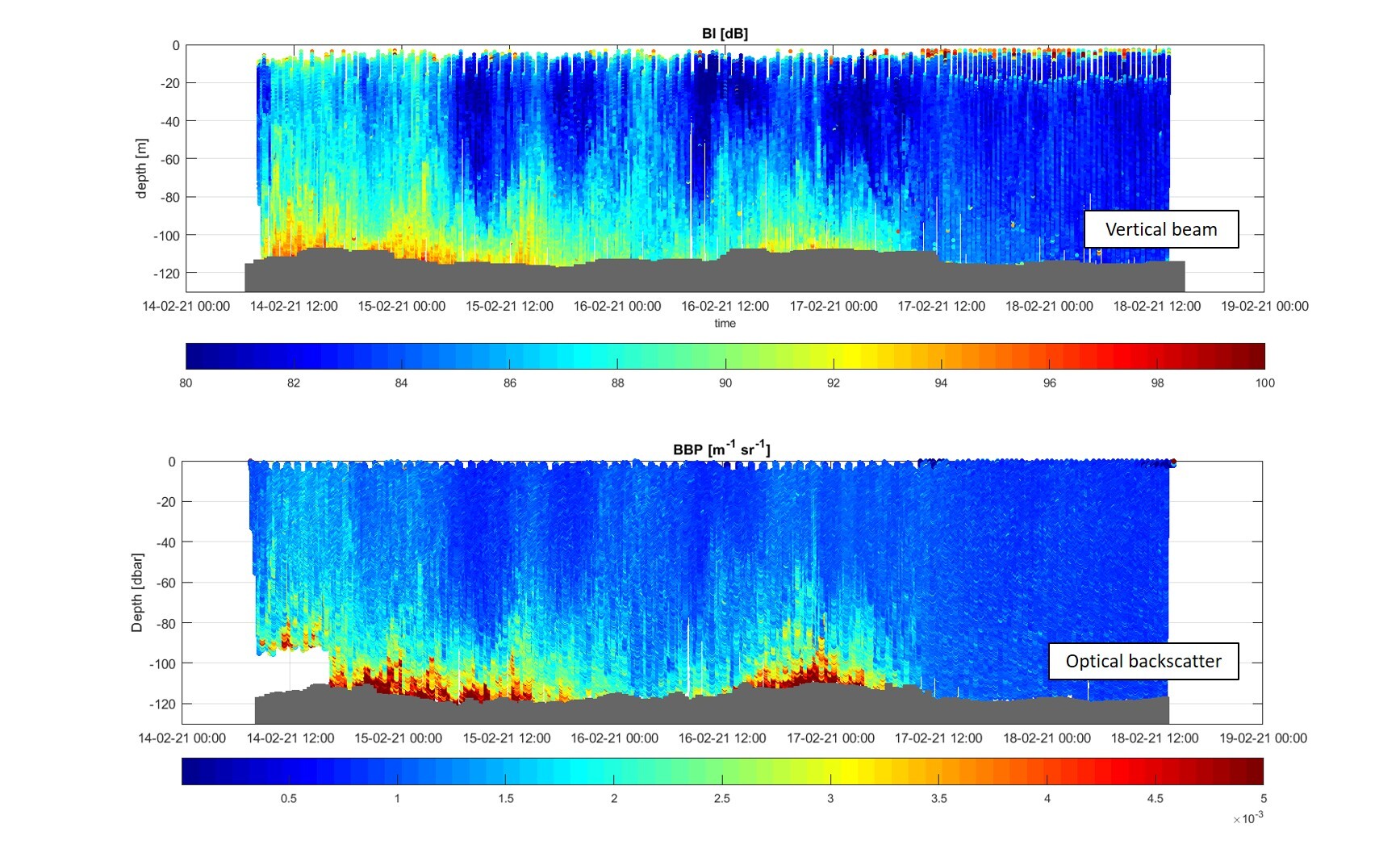

Whereas Figures 2 and 3 show current profiles obtained by the ADCP on the SeaExplorer glider across 60 km in the northwest Mediterranean, Figures 4 and 5 show data obtained following a deployment of a SeaExplorer glider equipped with an ADCP in a relatively shallow coastal area where variability within a short timescale is prevalent.

Figure 4 shows how the ADCP was recently able to measure tidal currents in considerable detail through the depth profile in the Atlantic off northwest France.

Meanwhile, Figure 5 illustrates how water turbidity measurements taken using the ADCP during the same mission match up very closely to those obtained conventionally using optical instruments. This was a major success, demonstrating the high quality of both Nortek’s ADCP technology and Alseamar’s data-processing skills (see below for more on turbidity).

Improving real-time data interpretation from ADCP glider missions still further

But configuring the ADCP-equipped underwater glider to gather vast amounts of usable oceanographic data is not the end of the story. While it’s straightforward to store the data from all the glider’s instruments on board and then download it when the glider returns to base at the end of its mission, accessing it during the mission is not.

“One big remaining challenge is to get access to as much of that data as possible in real time – something that is vital for our customers in the oil and gas industry, for example,” Orens de Fommervault says.

The glider can transmit data each time it reaches the surface, but it’s not practical for it to stay there long enough to offload all the data from its dive, given the low transfer rates possible in remote locations using satellite communications.

“The glider would have to spend most of its time at the surface to send all the data and would end up doing very little actual profiling,” he says.

So, the challenge has been to devise algorithms that could provide high-quality results while using as little data as possible. Getting the balance right is vital – if you transmit too little data, you risk having insufficient information to provide a complete profile across the glider’s trajectory.

Alseamar has made considerable progress with this already, and is currently working to improve real-time data interpretation still further, de Fommervault says.

Video: See how the SeaExplorer underwater glider was operated at the ODYSSEA Project’s observatories based in Al Hoceima in Morocco and in the Thracian Sea in Greece.

Measuring water turbidity with ADCPs – a new frontier for the energy industry

Another current area of focus for Alseamar with the ADCP is developing more accurate profiling of water turbidity – a function of particular interest for oil and gas companies seeking to identify promising subsea areas to explore for hydrocarbons by identifying bubbles of gas seeping into the water from the seabed.

The glider is already proving popular among Alseamar’s customers. Such additional functionality will broaden its appeal still further.

Video: The SeaExplorer is a powerful autonomous sensing platform dedicated to collecting water-column data profiles with very large spatio-temporal coverage (from regional to local scale). Driven by changes in buoyancy, the vehicle silently glides without wings, facilitating launch and recovery operations, avoiding wing breaks and limiting risks of entanglements.